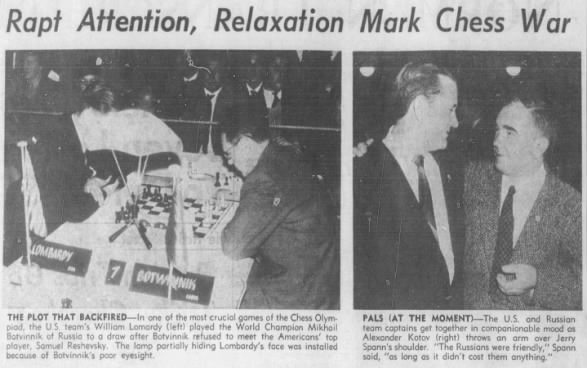

The Norman Transcript, Norman, Oklahoma, Sunday, November 09, 1958 - Page 2 — Rapt Attention, Relaxation Mark Chess War — The Plot That Backfired—In one of the most crucial games of the Chess Olympiad, the U.S. team's William Lombardy (left) played the World Champion Mikhail Botvinnik of Russia to a draw after Botvinnik refused to meet the Americans' top player, Samuel Reshevsky. The lamp partially hiding Lombardy's face was installed because of Botvinnik's poor eyesight.

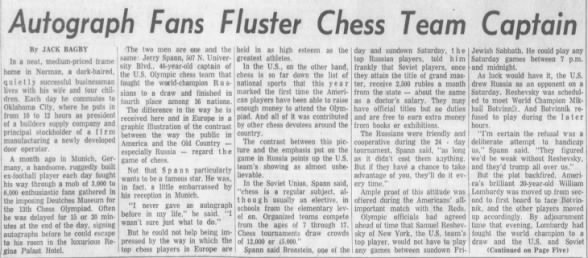

Pals (At The Moment)—The U.S. and Russian team captains get together in companionable mood as Alexander Kotov (right) throws an arm over Jerry Spann's shoulder. “The Russians were friendly,” Spann said, “as long as it didn't cost them anything.”

Rapt Attention, Relaxation Mark Chess War 09 Nov 1958, Sun The Norman Transcript (Norman, Oklahoma) Newspapers.com

Rapt Attention, Relaxation Mark Chess War 09 Nov 1958, Sun The Norman Transcript (Norman, Oklahoma) Newspapers.com

Autograph Fans Fluster Chess Team Captain by Jack Bagby — In a neat, medium-priced frame home in Norman, a dark-haired, quietly successful businessman lives with his wife and four children. Each day he commutes to Oklahoma City, where he puts in from 10 to 12 hours as president of a builders supply company and principal stockholder of a firm manufacturing a newly developed door operator.

A month ago in Munich, Germany, a handsome, ruggedly built ex-football player each day fought his way through a mob of 3,000 to 6,000 enthusiastic fans gathered in the imposing Deutsches Museum for the 13th Chess Olympiad. Often he was delayed for 15 or 20 minutes at the end of the day, signing autographs before he could escape to his room in the luxurious Regina Palast Hotel.

The two men are one and the same: Jerry Spann, 507 N. University Blvd., 46-year-old captain of the U.S. Olympic chess team that fought the world-champion Russians to a draw and finished in fourth place among 36 nations.

The difference in the way he is received here and in Europe is a graphic illustration of the contrast between the way the public in America and the Old Country — especially Russia — regard the game of chess.

Not that Spann particularly wants to be a famous star. He was, in fact, a little embarrassed by his reception in Munich.

“I never gave an autograph before in my life,” he said. “I wasn't sure just what to do.”

But he could not help being impressed by the way in which the top chess players in Europe are held in as high esteem as the greatest athletes.

In the U.S., on the other hand, chess is so far down the list of national sports that this year marked the first time the American players have been able to raise enough money to attend the Olympiad. And all of it was contributed by other chess devotees around the country.

The contrast between this picture and the emphasis put on the game in Russia points up the U.S. team's showing as almost unbelievable.

In the Soviet Union, Spann said, “chess is a regular subject, although usually an elective, in schools from the elementary level on. Organized teams compete from the ages of 7 through 17. Chess tournaments draw crowds of 12,000 or 15,000.

Spann and Bronstein, one of the top Russian players, told him frankly that Soviet players, once they attain the title of grand master, receive 2,500 rubles a month from the state — about the same as a doctor's salary. They may have official titles but no duties and are free to earn extra money from books or exhibitions.

The Russians were friendly and cooperative during the 24-game tournament, Spann said, “as long as it didn't cost them anything. But if they have a chance to take advantage of you, they'll do it every time.”

Ample proof of this attitude was offered during the Americans' all-important match with the Reds.

Olympic officials had agreed ahead of time that Samuel Reshevsky of New York, the U.S. team's top player, would not have to play any games between sundown Friday and sundown Saturday, the Jewish Sabbath. He could play any Saturday games between 7 p.m. and midnight.

As luck would have it, the U.S. drew Russia as an opponent on a Saturday, Reshevsky was scheduled to meet World Champion Mikhail Botvinnik. And Botvinnik, refused to play during the later hours.

“I'm certain the refusal was a deliberate attempt to handicap us,” Spann said. “They figured we'd be weak without Reshevsky, and they'd trump all over us.”

But the plot backfired. America's brilliant 20-year-old William Lombardy was moved up from second to first board to face Botvinnik, and the other players moved up accordingly. By adjournment time that evening, Lombardy had fought the world champion to a draw and the U.S. and Soviet teams were even, 3-2, in other games. Russia settled for a draw and conceded a great moral victory to the U.S. team.

Ironically, Spann said, a later analysis of the Lombardy-Botvinnik game showed that Lombardy was leading and would have won the match if it had been played to its conclusion.

Despite the two-day loss of Lombardy, when his borrowed automobile skidded on wet cobblestones and crashed through the window of a flower pavilion, the U.S. team kept on winning. But the Russians won a greater number and ended with a final high score of 34½ won, 9½ lost. Yugoslavia was second, 29-15, followed by Argentina, 25½-18½, and the U.S. 24-20.

Autograph Fans Fluster Chess Team Captain 09 Nov 1958, Sun The Norman Transcript (Norman, Oklahoma) Newspapers.com

Autograph Fans Fluster Chess Team Captain 09 Nov 1958, Sun The Norman Transcript (Norman, Oklahoma) Newspapers.com

Spann: Chess, Football Alike 09 Nov 1958, Sun The Norman Transcript (Norman, Oklahoma) Newspapers.com

Spann: Chess, Football Alike 09 Nov 1958, Sun The Norman Transcript (Norman, Oklahoma) Newspapers.com